|

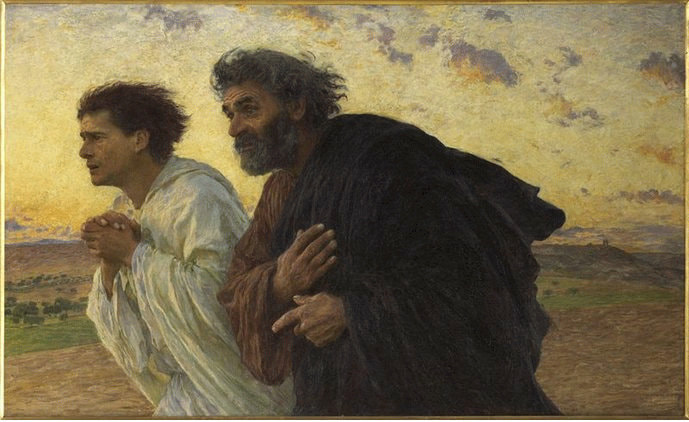

John 20:1-9 (NRSVCE) Early on the first day of the week, while it was still dark, Mary Magdalene came to the tomb and saw that the stone had been removed from the tomb. So she ran and went to Simon Peter and the other disciple, the one whom Jesus loved, and said to them, “They have taken the Lord out of the tomb, and we do not know where they have laid him.” Then Peter and the other disciple set out and went toward the tomb. The two were running together, but the other disciple outran Peter and reached the tomb first. He bent down to look in and saw the linen wrappings lying there, but he did not go in. Then Simon Peter came, following him, and went into the tomb. He saw the linen wrappings lying there, and the cloth that had been on Jesus’ head, not lying with the linen wrappings but rolled up in a place by itself. Then the other disciple, who reached the tomb first, also went in, and he saw and believed; for as yet they did not understand the scripture, that he must rise from the dead. This is perhaps the most important passage in Scripture, as it’s where we find out that John is a faster runner than Peter. I’m not quite sure why that’s important, but John sure thought it was important enough to mention that Peter wasn’t as fast as he was.

More seriously though, that bit of this passage does seem to tell us something. All throughout his Gospel, John refers to himself as “the beloved disciple.” He is the one who Jesus loved most, he is the one who laid his head on Jesus' breast. He is the closest to Christ of any of the disciples. So when he heard Jesus’ body was missing, he was the most concerned. We can imagine John and Peter both taking off running, but John being completely overtaken by emotion was not even aware of how out of breath he was or how sore his legs were. His only concern in the entire world at that moment was Jesus. And so he arrived at the tomb first. But notice that he does not enter right away. He merely peeks his head in. He arrived at the tomb first, but the first person to enter is Peter. John, the beloved disciple and the closest to Christ, waits for Peter to enter before entering himself. Even Mary Magdalene, the first to see the empty tomb, does not enter. She too waits for Peter. There’s something about Peter which makes both John and Mary defer to him. Peter was first among the disciples. Christ placed him at the helm. When he made the ultimate proclamation “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God" (Matthew 16:16), Christ gives him the name Peter, and proclaims that he is the rock upon which the Church will be built. Even though Peter gets rebuked shortly after, and even though Peter is the one who denied Christ three times, he remains in a position of authority and leadership among the disciples. And even though the beloved disciple was closer to Christ than Peter was, he remembers Peter’s role and defers to him. There is, of course, the simple literary play here. Luke had already recorded in his Gospel by this time that Peter was the first to enter the tomb. John, writing his Gospel later, obviously didnt want to contradict Luke, so he has himself arriving first but Peter still entering first. But the message he is conveying is the same. Christ has called Peter to a particular vocation, to lead the disciples. John knows this, and respects Christ’s decision. So he defers to Peter. This is not so much about consistency of Scripture, or who is more important, or who is more loved. It’s about vocations. John, beloved as he was, was not called to a vocation of the same kind as Peter, nor was Mary. Peter’s vocation was unique We all have our own vocations, the life that God calls us to. And no matter what life we are called to, though it may be similar to those of other people (as John remains an Apostle like Peter, even if he is not the leader), it will be in a special way unique to each of us. Our role is to trust in Christ to provide the vocation most fitting for us, to lean on him in discerning the life we are to lead, and by the grace of God to faithfully live out that vocation to the best of our ability. Peter was not the beloved disciple, but that does not mean he is not in his own way special. So too we each have our roles to play. It is up to us to respond to those callings, as the disciples did. It’s Holy Saturday, which means there are no readings in today’s lectionary. Christ has been crucified, and is now absent. We await his resurrection. But he’s certainly not idle during this time. Remember what the Apostles Creed says: “[Jesus] suffered under Pontius Pilate; was crucified, dead and buried: He descended into hell.” It is now, between the crucifixion and the resurrection, that Christ made his descent to the limbo of the Fathers and freed the righteous souls who were waiting there. Abraham, Moses, Jacob, Joshua, Isaac, Ezekiel, Isaiah, and all the righteous who died before Christ, the Way to salvation, was made perfect.

More commonly, this event is known as the Harrowing of Hell, when Christ broke open the doors to Hell and made salvation possible. But we don’t have much information about it in Scripture. Many have thought about what this must have been like for the souls in waiting. Perhaps the most famous musing on this comes from Dante, where he has Virgil, Dante’s guide and one of the righteous pagans who was nonetheless left in hell after the Harrowing, point to a hole in the wall and describe a man who broke through and took many souls with him through the exit. This account is very well-known, but I must admit it has a very Kool-Aid Man vibe to it. Dante is of course taking some artistic liberties with what has been passed on through the deposit of the faith. The Church Fathers agreed on the purpose of the Harrowing: Christ was there to liberate the souls of those who died in a state of grace prior to his death and resurrection. That was the dominant (though not sole) view on the Harrowing for most of Christian history. Other views, like that of John Calvin in the 17th Century, disagree with that. The thought that Jesus needed to go down to liberate some souls in waiting was childish and silly to Calvin. He held that instead the soul of Christ descended in order to experience the torments of hell (that is, not Abraham’s Bosom, but the actual hell of the damned). “If Christ had died only a bodily death, it would have been ineffectual. No — it was expedient at the same time for him to undergo the severity of God’s vengeance, to appease his wrath and satisfy his just judgment. For this reason, he must also grapple hand to hand with the armies of hell and the dread of everlasting death.” -John Calvin (Institutes, II, XVI, X) This reading, of course, is grounded primarily in Calvin’s soteriology. He believes the atonement is first and foremost a satisfying of God’s wrath—of the Father unleashing the fullness of His wrath on the Son, and thus there is effectively no wrath left for us (Christ takes it all). If that’s what you think atonement is, then it makes sense to think this suffering must be all-encompassing (or else what does “it is finished" really mean?). I, of course, disagree with that view (of both the Harrowing and atonement). But now isn't really the time to hash out soteriological disagreements. Christ has been crucified, and we await his resurrection. That we are saved by Jesus' action on the cross is clear from our previous readings. But the hope we have as Christians is not in the crucifixion, but in the resurrection. That’s why, in the Nicene Creed, we say “I look forward to the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come.” We await Christ’s resurrection, for it is in that event that we are given hope of our own future life, of our own resurrection and perfection, so that we may too ascend and join Jesus in the presence of the Father. Hebrews 4:14-16, 5:7-9 (NRSVCE) Since, then, we have a great high priest who has passed through the heavens, Jesus, the Son of God, let us hold fast to our confession. For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but we have one who in every respect has been tested as we are, yet without sin. Let us therefore approach the throne of grace with boldness, so that we may receive mercy and find grace to help in time of need. In the days of his flesh, Jesus offered up prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears, to the one who was able to save him from death, and he was heard because of his reverent submission. Although he was a Son, he learned obedience through what he suffered; and having been made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation for all who obey him, It’s Good Friday, the day when we remember the crucifixion of our Lord. The day when the Son was lifted up on the cross, and in obedience to the Father died for our sins. The true humanity of Christ is more evident in that event than anywhere else in Scripture. It’s fitting, then, that we have this reading from the letter to the Hebrews which focuses on the humanity of Christ, and the implications that has for our own salvation.

Jesus is the high priest, who stands before us showing the path to salvation. But he is not like the other high priests, who are raised so high above the common man so as to be completely disconnected from him. High priests are too far removed—they don’t understand the needs of the people. They would enter into the Holy of Holies once a year, behind the veil and into the presence of the Ark. Jesus is unique. He is just like us, in every way except sin. He shares in the struggles of man, he was tempted, he felt pain, he felt heartache, he felt strife. And more than that, Jesus did not pass behind the veil into the presence of the Ark, but rather he passed through the heavens into the very presence of the Father directly! There is no other high priest like him! Through his obedience to the Father, he was able to overcome that human weakness which he shares with us, and he was made perfect and thus dwells with the Father. Where Adam had failed, Jesus succeeds. Thus, he has become the eternal High Priest and “he became the source of eternal salvation for all who obey him.” The high priests can offer no true help to the common man. They are ignorant of the struggles of normal men. But Jesus is able to offer a helping hand. Jesus knows precisely what we need. The fact that he can sympathize with our condition and our situation means we can approach him in confidence. We can know that Jesus can help. We know that in Jesus we will receive the mercy and grace that we need. Not only is Jesus the model for human obedience to the divine will, the paradigm which we must imitate, but he is also the divine hand which reaches forth and carries us along. The dual natures of Christ are quite important here. He is living proof that man can be saved, man can be made perfect (that is, made complete by fully becoming what we were created to be, and dwelling with Christ in the presence of the Father), and he has opened up the path to salvation for all men. He is the Way. That is why the cross is the center point of the entire Christian faith. It is on the cross that our salvation is made possible. And so today, on this Good Friday, we remember the day that Jesus died. We remember the day he said “It is finished.” 1 Corinthians 11:23-26 (NABRE) For I received from the Lord what I also handed on to you, that the Lord Jesus, on the night he was handed over, took bread, and, after he had given thanks, broke it and said, “This is my body that is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” In the same way also the cup, after supper, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.” For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the death of the Lord until he comes. I switched Bible translations today. Did you notice? I went with NABRE because I want to highlight one thing in this passage. Most English translations are going to start this out with “on the night he was betrayed”, and our minds immediately go to Judas, who betrayed Jesus on the night of the Last Supper. That’s certainly not a wrong translation, by any means. It highlights which day on which this was occurring, and emphasizing that Jesus was crucified because of man’s betrayal. But using “betrayal” there seems to impose the image of Judas onto the text, when it isn’t necessarily there in the Greek.

The Greek word there is paradidomi, which literally means to be handed over. Certainly that can mean betrayal, as you can be handed over to the authorities. But it doesn’t necessarily have that connotation. For example, in the Spanish Reina Valera translations, it gets rendered as fue entregado, or “was delivered.” I’m not going to get into a quibble about how best to translate it, as I’m far from qualified to go up against Biblical scholars on that one. But I think the language of deliverance or handing over highlights another aspect of this verse. Remember that Paul is admonishing the Corinthians for not giving the Lord’s Supper the reverence it is due. They are allowing social class systems of their lives to define the communal supper. The rich among them arrive already drunk, as they were able to eat and drink all day while the poor had to work. They do not eat together, but instead the rich eat with the rich and the poor with the poor. This is no communal table at all! If we focus on that context, we can see how rendering paradidomi as “handed over” may be beneficial. For who was it, ultimately, who handed Christ over to be crucified? Who was it who sent him? It was the Father! Indeed, this even echoes what Paul writes to the Romans, when he says “He who did not spare his own Son but handed him over for us all” (Romans 8:32). And John the Evangelist, when he says that God so loved the world he gave His only-begotten Son (John 3:16). Paul is emphasizing here the seriousness of the Lord’s Supper. He focuses in on the fact that this is, indeed, the Son who was sent by the Father, who was handed over for our sins. This is no mere meal. That is why his warnings come swiftly afterward. “This is why many among you are ill and infirm, and a considerable number are dying.” Because you are receiving unworthily. You are not approaching the Lord’s Supper with the proper discernment of what it is: the Body and Blood of Christ, the one who was handed over. Tonight, on Maundy Thursday, we remember the Last Supper, the night Jesus was handed over for our sins. I pray that we may all be discerning in our reception of the Holy Eucharist, and that none of us receive unworthily. I pray that we all remember what it is we do, that in joining together in the Lord's Supper we may all be joined together with Christ, as the disciples were. Isaiah 50:4-9a (NRSVCE) The Lord God has given me the tongue of a teacher, that I may know how to sustain the weary with a word. Morning by morning he wakens-- wakens my ear to listen as those who are taught. The Lord God has opened my ear, and I was not rebellious, I did not turn backward. I gave my back to those who struck me, and my cheeks to those who pulled out the beard; I did not hide my face from insult and spitting. The Lord God helps me; therefore I have not been disgraced; therefore I have set my face like flint, and I know that I shall not be put to shame; he who vindicates me is near. Who will contend with me? Let us stand up together. Who are my adversaries? Let them confront me. It is the Lord God who helps me; who will declare me guilty? This almost reads as if Isaiah is trying to convince himself, as much as he is trying to teach the audience. Not only is he trying to make sense of the communal pains of a life lived in exile, the pains of a nation without a land to call home, but he is trying to make sense of the persecution and pain he has personally suffered as a prophet in a foreign land. He has been given the great gift of good teaching, in order to fulfill what God has called him to do. But because of this he has been mocked, spit on, and beaten. He has faced constant hardships because of his calling. But he tells us that he endures all of that, without even providing resistance (“I did not hide my face”), because he has faith that what he is doing is righteous and just. He has faith that whatever happens to him is God’s will. No matter how much people may persecute and judge him, the true Judge is the only one who matters. “It is the Lord God who helps me; who will declare me guilty?”

It takes a tremendous amount of resolve and faith to do what Isaiah did, and I wonder how many of us would be able to do the same. Could we endure constant mockery, constant attack, constant fearing for who might come after us next, all because of who we are? What must it be like to walk down the street and be accosted by everyone you see, for no reason other than it is you? I have had the luxury of growing up a white male middle class American in the late 20th century, so I have never had to endure persecution of any kind. I don’t know how I would deal with that even on a small scale, let alone a constant barrage. I would love to say my faith is strong enough to cling to God through something like that, but I fear that it is not. And I think Isaiah feared that as well. I think Isaiah is worried his resolve is beginning to fail due to the endless assault. He knows why he must endure, but he is praying for the strength to be able to do so. He is clinging to God with everything he has left, and asking God to carry him through the trouble. I can’t help but think of the people today who still deal with that kind of persecution. I pray that they are graced with the strength of faith and resolve to endure, like Isaiah and the people in exile were. I pray that they are able to cling to God through those times, and find strength and purpose in Him. I don’t know what it’s like to be persecuted, and I pray that one day, every person will be able to join me in that ignorance. Isaiah 49:1-6 (NRSVCE) Listen to me, O coastlands, pay attention, you peoples from far away! The Lord called me before I was born, while I was in my mother’s womb he named me. He made my mouth like a sharp sword, in the shadow of his hand he hid me; he made me a polished arrow, in his quiver he hid me away. And he said to me, “You are my servant, Israel, in whom I will be glorified.” But I said, “I have labored in vain, I have spent my strength for nothing and vanity; yet surely my cause is with the Lord, and my reward with my God.” And now the Lord says, who formed me in the womb to be his servant, to bring Jacob back to him, and that Israel might be gathered to him, for I am honored in the sight of the Lord, and my God has become my strength-- he says, “It is too light a thing that you should be my servant to raise up the tribes of Jacob and to restore the survivors of Israel; I will give you as a light to the nations, that my salvation may reach to the end of the earth.” Isaiah describes how God appoints His servants. He prepares them even while they are still in the womb, ordaining them for the service they will live out. God provides them with everything they will need to fulfill their calling. He gave to Isaiah a sharp tongue, and made him like a polished arrow that is true to its target. But He also keeps His servants hidden, and protected, until the proper time. I can’t help but recall Jesus here, repeatedly telling his disciples to not tell anyone about the wonders they saw while traveling with him because his time had not yet come. Over and over again, Jesus would perform miracles, but he would ask that nobody tell until his time had come. When his miracles finally were made known, when he started to earn a reputation, the leaders saw him immediately for what he was: a threat to their power and authority. They hated him, and sought to kill him. His time had come, and all was revealed in his crucifixion and resurrection.

But notice the second half of this passage, Isaiah returns to the “light to the nations” language we saw yesterday, but in a different context. This time, he addresses head on the plight of the Jews in exile. They are scattered to the winds, scraping by in foreign lands. Surely God has abandoned them! Surely they have failed due to their sin, and so will never see Israel restored again! But Isaiah provides reassurance to an exiled Israel. God chose me before I was born and made me into the prophet I am, and now God calls Israel. The language of the womb and birth here is not incidental. Isaiah is talking about a rebirth of Israel. Israel did sin, yes. And Israel was conquered by the Babylonians and scattered, yes. But God calls them back, from all corners of the world. He gathers the widespread tribes back to Himself, back into one People of God, into one Israel. This is a message of hope to a people in exile. But more than hope, it is a call to service. The scattered people are like dim lights flickering in the night. God doesn’t call them all together merely to save the light that is left. God calls them all together to once again to strengthen that light, so that they might become His shining beacon. They will be a light to the nations, a light that propagates God’s plan of salvation. Israel, and by extension all of us, are here with a purpose. We are not only focused on our own walk of faith and our own salvation. We are here to fulfill our calling to evangelize the world, to bring God’s Light which has been given to us and shine it in every corner and nook and cranny. Like Isaiah, and like the people in exile, we are called to service. It’s our duty to answer that call. Isaiah 42:1-7 (NRSVCE) Here is my servant, whom I uphold, my chosen, in whom my soul delights; I have put my spirit upon him; he will bring forth justice to the nations. He will not cry or lift up his voice, or make it heard in the street; a bruised reed he will not break, and a dimly burning wick he will not quench; he will faithfully bring forth justice. He will not grow faint or be crushed until he has established justice in the earth; and the coastlands wait for his teaching. Thus says God, the Lord, who created the heavens and stretched them out, who spread out the earth and what comes from it, who gives breath to the people upon it and spirit to those who walk in it: I am the Lord, I have called you in righteousness, I have taken you by the hand and kept you; I have given you as a covenant to the people, a light to the nations, to open the eyes that are blind, to bring out the prisoners from the dungeon, from the prison those who sit in darkness. There’s something that strikes me as odd in this passage, and it’s right in the last few lines. The Lord has made His people a “light to the nations”, a light that is meant to open the eyes of the blind. That is, to open the eyes of those who do not believe. Those who don’t believe are like prisoners in a dark dungeon, unable to leave. God’s people have been shown the Light of the World, and having been made bringers of the Light themselves they are to illumine the dark dungeons, in order to bring the prisoners out into the Light.

That imagery of prisoners in a dungeon unable (or even perhaps unwilling) to get out, because they do not have the Light, sounds eerily familiar. I don’t know about you, but my mind immediately went to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. Of course, the writer of Isaiah is not making a reference to the Cave here, as that won’t be written for several more centuries at the time when he’s writing, but the similarities are intriguing. Plato envisions prisoners tied up in a cave such they cannot move, they can’t even turn their heads. They can only stare at the wall in front of them, forever. Behind them is a great flame, and between the flame and the prisoners are a bunch of moving figures (think stick puppets). The flame casts shadows of these figures on the wall, and all the prisoners can do is watch the shadows, pontificate about the shadows, form opinions about what the shadows might be or why the behave the way they do. For the prisoners, those shadows are everything in the world. And they content themselves with that reality. The thought of anything beyond the shadows is ridiculous. But one of the prisoners gets free. He is able to stand up, and turn around. He sees that the shadows are not the world, but are just imitating the real objects, the stick puppets. And the stick puppets aren’t the source of the shadows, so much as they are being acted upon by the flame. The flame is the ultimate source of all that exists, so it would seem. But then the prisoner sees another light off to one side, and he begins to follow it. He climbs and climbs, stumbling and clawing his way toward this mysterious light. Until finally he emerges outside the cave, and is blinded by the intensity of the light. When his eyes finally adjust, he sees a world full of color and life. Grass and trees and animals. Surely this is far more real than what he knew in the cave! He notices, though, that some of these real objects have shadows too. So he looks for the flame that causes them. He looks to the sky and sees the sun, what must be the source of light and life for everything that is! He has finally seen the true Light! In his eagerness, he rushes back into the cave. He needs to illumine the minds of his prisoner friends! They must come to see the Light! But when he tells them, they scoff and laugh. They mock him. What a ridiculous proposal! How could there be more than these shadows?! We want nothing to do with your so-called Light! We are happy in darkness! Plato uses this allegory as an example of what it’s like to be a philosopher, and share the knowledge one has gained with those who still “dwell in darkness.” Isaiah is using a similar analogy, but instead of the philosopher’s truths, it’s the divinely-revealed truths of God which we are trying to share with those stuck in the cave. It’s the call to evangelize the world, and the difficulty that we will face in doing so. We will be mocked, we will meet resistance, perhaps even violent resistance. Those who have spent their whole lives in darkness will often want nothing to do with the Light—they are content in darkness. But God has set us forth with a purpose, to illumine the world. So no matter how difficult it may be, we must continue to shine. Not just for our sake, but for the sake of those still in darkness who God also loves and with whom He wishes to share His light. Philippians 2:6-11 (NRSVCE) Christ Jesus, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death-- even death on a cross. Therefore God also highly exalted him and gave him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bend, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father. It’s Palm Sunday today, the day when we commemorate Christ’s very public entrance into Jerusalem, and the day which leads us into Holy Week. We heard the full Passion narrative at mass today, but before we got there we heard St. Paul with his Christological hymn in his letter to the Philippians. This passage is especially important as we approach Easter, but it’s also relevant to a few things we have already reflected on this Lent.

Recall when we talked just a few days ago about how God desires relationship with us. God is not some absent heavenly monarch who demands obedience and worship from us from up on His throne. God desires closeness with man, so much so that when man was falling away the Son was willing to lower himself to the point of even becoming man. He was in the form of God, but he did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited. Meaning the Son did not seek to use His divine power and authority to impose His will on the world, to demand the world’s submission, indeed even to force it to be so. Rather, He desired relationship. He desired closeness. Because of His love for man and for all Creation, he took on the weak and miserable human condition. This is not as you might see in pagan religions either. Plenty of pagan gods are said to have “come in human likeness”, as a sort of disguise that helps them deceive actual humans. Unlike those pagan gods, who are “like” man in appearance only, Jesus truly is man in his very nature. Fully man, and fully God. It’s a closeness which is almost too incredible to believe! Because of His deep love for us, for you and me, God was willing to become one of us, even to die like one of us, all for our sake. It’s the central message of the Gospels, and the truth upon which all of Christianity hinges. Pope Benedict XVI has spoken about this passage in terms of descent and ascent. We first have the descent, of the Son emptying Himself and becoming man, in obedience to the will of the Father. That obedience carries through to His Passion, and to the Crucifixion. That obedience is why, when we see the risen Christ at the Resurrection, God exalts him above all. We see the ascent, and the Son rejoining the Father in glory. Jesus has been given the name of Lord, a name which places him as the king of all Creation, so that all knees shall bend and all heads shall bow before him. The Holy Father says, “In the Son, the project of salvation reaches fulfilment and the faithful are invited, especially in the liturgy, to announce and to live the fruits [of salvation].” The project of salvation is complete through Christ’s obedience. So too our own salvation comes from obedience, through our confession that Jesus Christ is Lord, and all the implication thereof. If we truly confess that Christ is Lord, our knees will bend, our heads will bow, and we will proclaim the glory of His name above all other names. Ezekiel 37:21-28 (NRSVCE)

Ezekiel prophesies that God will unite the divided kingdoms of Judah and Samaria, and unite them into one kingdom under David, the one king. But we can easily see how this is also a prophesy for the true King, Jesus, who unites the two kingdoms (the Jews and the Gentiles) under Himself. This connection is explicitly made by John in today´s Gospel reading. But since we covered that one during Lent last year, I won’t dwell too much on it this time around.

Notice how overt the references to Christ become in the second half of this passage. God will make an everlasting covenant of peace with Israel. Jesus is, of course, the Prince of Peace who establishes the New Covenant which does not end. God sets His dwelling place among Israel, which we know is a reference to the Incarnation, in which the Son comes to dwell among men as man, forever. The nations will know that the Lord sanctifies Israel because He dwells among them. Sanctification is tied explicitly to the closeness of God to man. As we approach God, we are sanctified. We’ve discussed this a few times so far this Lent, about how through sanctification and following Christ on the path to the source of our being (namely, God) we more fully become who we are. Our sins and imperfections fall away in this process of sanctification. The Law was given to Israel to set them apart, so that by adhering to it they would become more holy. How much more we are able to do this when it is not only a law that was given, but God himself who was given to us? In Jesus, God has never before been closer to man. He is so united to man that the Son truly is man Himself. So how much more are we able to be sanctified so long as we cleave to our King? So long as we follow close to our Good Shepherd? One of the ways we must follow is, of course, through imitation. Jesus is both perfectly holy and fully man, so who better to imitate? But remember that the holiness of Jesus, the closeness of Jesus to the Father and the tightness of his will and the Father’s will, meant that Jesus was ready to lay down his life for others and for God. Are we so willing? It’s easy to say we are, and it’s easy to imagine a scenario in which you lay down your life for your friends and family, or for your faith. But if it were to come down to it, how many of us would actually be ready to do that? Martyrdom is not a pleasant subject to talk about, but it is a reality that Christians throughout history and even today have to face. Countless Christians have been persecuted for their faith, and countless have died. We have the luxury in America of living in a society built, largely, by Christians. So persecution isn’t really a concern, and martyrdom is completely off the radar. But that’s the level of imitation we need. Christ died for us, Christ was persecuted for us, Christ was brutalized for us. Would we be so willing to do the same for him? Jeremiah 20:10-13 (NRSVCE)

There’s something about reading the many laments in the Bible that helps elucidate the kind of relationship we are meant to have with God. We go to church and it seems like most of the hymns and songs we sing are praise, so it’s nothing but praise that we take home with us. Don’t get me wrong, we ought to praise God, in all things. Jeremiah even works some praise into this prayer. But a relationship based purely on praise is very one-dimensional, and not really the kind of relationships laid out for us in Scripture. We see Jeremiah in the middle of his laments, crying out in frustration and confusion. He has been tasked by God to preach God’s message to the people, to convert them. But the people are unresponsive and prefer instead to conspire to kill him. His frustration reaches a crescendo in this chapter. “Cursed be the day on which I was born! Why did I come forth from the womb to see toil and sorrow and spend my days in shame?” (Jeremiah 20:14a, 18).

This manner of prayer is echoed in the Psalms many times over. This is not a man lofting petitions at a monarch looking down from his throne, or, as is oddly common in prayers, simply describing God over and over again. Often we hear prayers that are barely more than “God, you are so big and great. You are so great. You are so big. And we love that you are both so big, and so great!” How often have you prayed that yourself? I know I have! But the example we see in Jeremiah here, and in the Psalms, is not so impersonal, not so disconnected. This is a man baring everything which is weighing down on his heart to the One who he knows will listen with a loving ear. This is not so much a petition as it is Jeremiah trying to explain to God how he feels. This is what happens in true relationship. You communicate, you petition, you praise, and yes, you lament. You put your heart and soul into that relationship, which includes the whole spectrum of human emotion, even frustration. Sometimes you will go to pray and you won’t have anything to say at all. And that’s fine! When you are with family or friends, are you all constantly chattering? Has there never been just a pleasant moment of silence among you? It’s okay to simply want to rest in the presence of God. Indeed, this is something which ought to be part of our regular prayer lives. And sometimes, like Jeremiah, the things you have to say may be cries of anguish and frustration, cries of confusion and desperation. “Why did you even allow me to be born when you knew it was going to be like this?” And that’s okay, too. God desires relationship with you, and you can’t have a true loving relationship if you are not ready to voice your worries and your concerns to Him. Jeremiah, the weeping prophet, sets an example for us. It’s okay to be frustrated with what God asks of you. Pray about it. |

ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed