|

2 Corinthians 5:17-21 (NRSVCE) So if anyone is in Christ, there is a new creation: everything old has passed away; see, everything has become new! All this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ, and has given us the ministry of reconciliation; that is, in Christ God was reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them, and entrusting the message of reconciliation to us. So we are ambassadors for Christ, since God is making his appeal through us; we entreat you on behalf of Christ, be reconciled to God. For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God. Christ came to reconcile the world to God. That is, Christ, in whom we find a perfect unity between human and divine nature, calls us to unite with him so that we might also be joined with God. He has made it possible for us to become members of the one Body, with Christ at its head. And in so reconciling ourselves with the Body of Christ, we become reconciled to God. We become a new people, a new creation, shedding what is old (namely, our sin and vice) and being made anew.

But note what Paul says here, specifically. God entrusted the message of reconciliation to us, to His people. He has made us ambassadors for Christ, in this mission of reconciliation. The Good News we are to spread is not only that Christ has died and risen, but also that God is reconciling the world. God is calling all the world back to Himself. As ambassadors in this mission, we are to call others to be reconciled to God as well, just as Paul does here with the Corinthians. Entreating others to reconcile themselves with God ends up ringing hollow, though, if we are unable to reconcile with each other. It rather comes off as condemnatory, hostile, and particularly condescending. There’s probably someone in your life you disagree with all the time, vigorously even. You probably don’t get on very well. What would your response be if that person were to tell you that you need to get right with God? What would their response be if you told them the same? Surely not positive! I imagine the response would be one of anger, frustration, perhaps even outrage! How dare you presume to know my relationship with God! YOU are the one who needs reconciliation! That’s the trouble about being an ambassador. There’s a reason political ambassadors live in the nations they are ambassadors to, and it’s not simple logistics. You cannot succeed in an ambassador’s mission, indeed you cannot even really participate in it, unless you are willing to empathize, establish relationships, and truly try to reach people. Simply shouting “Get right with God!” at people is probably not going to help anyone. But in reconciling with those around you, you begin to fulfill that role as an ambassador for Christ. You who are reconciled with Christ, you who are a member of His Body, are their life raft. By reconciling with you, they will then begin to be able to reconcile with the whole Body, and thus become ambassadors themselves. This is not merely their business to take care of, and I think that’s the problem most street preachers can’t seem to overcome. This is your task, for you are already an ambassador and they are not. You are the one who must establish that relationship. You are the one who must introduce them to Christ. You are the one who must reconcile with them. Only then will you be able to say: “We entreat you on behalf of Christ, be reconciled to God.” Luke 18:9-14 (NRSVCE) He also told this parable to some who trusted in themselves that they were righteous and regarded others with contempt: “Two men went up to the temple to pray, one a Pharisee and the other a tax collector. The Pharisee, standing by himself, was praying thus, ‘God, I thank you that I am not like other people: thieves, rogues, adulterers, or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week; I give a tenth of all my income.’ But the tax collector, standing far off, would not even look up to heaven, but was beating his breast and saying, ‘God, be merciful to me, a sinner!’ I tell you, this man went down to his home justified rather than the other; for all who exalt themselves will be humbled, but all who humble themselves will be exalted.” Be like the tax collector. Don’t be like the Pharisee.

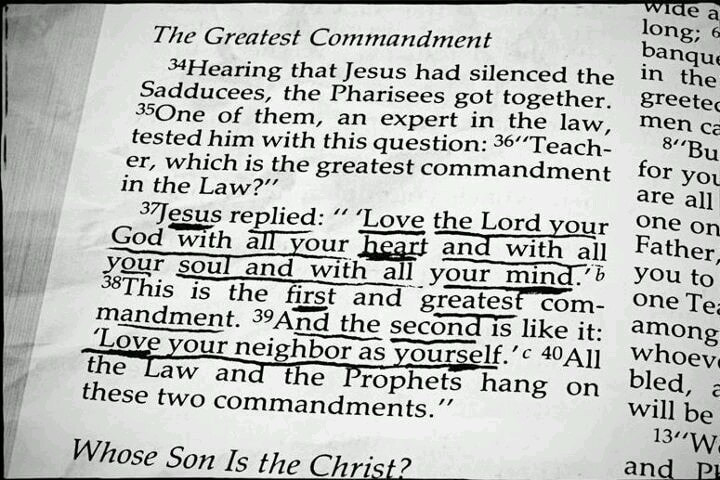

Surely that’s the message of this parable, no? That is at least what it appears to be, at a cursory glance. The Pharisee, the one who has a higher status by Temple law and thus thinks himself righteous, thanks God he is not like the wicked people outside the Temple. But the tax collector is one of those people, and Jesus clearly says that it is the tax collector, not the Pharisee, who is justified. So if that’s the case, we ought to want to be like the tax collector, so that we too are justified, and not like the Pharisee, who is not. The trouble with this is that the Pharisee’s prayer isn’t wrong, factually speaking. He thanks God that he is doing pious things, rather than engaging in wicked deeds. And he ought to thank God for that, as ought we all. He has set himself apart from others, which is what the word “holy” means, according to the Law that was given by God. And that’s a good and righteous thing to thank God for. By the standards of the Temple law, he is righteous. What’s wrong is not that he thanks God for being set apart, but that he ascribes his righteousness to himself. “I fast twice a week; I give a tenth of all my income.” He accomplished this. He may be addressing the Lord, but his focus is on himself. The problem is that his motivations make his prayer self-congratulatory. By his actions, he is not like those other people. He has set himself apart from the others, he has clearly demarcated the line between “us” and “them,” and he thanks God he is on the right side of that line. And thus you can see the issue with reading this parable as simply “Don’t be like the Pharisee” or merely “be humble.” We end up leaving this parable attempting to be just as self-congratulatory as the Pharisee is. “God, I thank you that I am not like the other people: self-righteous Pharisees and hypocrites.” Just as he did, we place divisions amongst ourselves, we label people as “us” and “them,” and we thank God we are not like “them.” The tax collector, on the other hand, came to God not to extoll the merits of his own accomplishments. He came asking for mercy, knowing that nothing he did or could do was worthy enough. His only hope was in mercy. He never asked to be like the righteous people, like the Pharisee who was in the Temple. He was too desperate for that. He needed God’s mercy before anything else. He couldn’t be bothered to divide humanity up like the Pharisee did. God’s people are to be holy, yes. They are to be set apart, yes. But it is not by any individual’s, or even any collective people’s actions that this is accomplished. It is God, first and foremost, who sets His people apart and makes them holy. That’s what the tax collector realized, and why he begs for mercy. But we are not to come away with this siding with the tax collector, or else we fall into the same trap of placing the divisions ourselves—of siding against the Pharisee. The message of the parable, at least as I read it, is not merely “Be humble” or “Don’t be like the Pharisee.” But rather it is that when we are the ones who try to mark that line between “us” and “them,” we find that God is never on our side of the line. Mark 12:28-34 (NRSVCE) One of the scribes came near and heard them disputing with one another, and seeing that he answered them well, he asked him, “Which commandment is the first of all?” Jesus answered, “The first is, ‘Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is one; you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength.’ The second is this, ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ There is no other commandment greater than these.” Then the scribe said to him, “You are right, Teacher; you have truly said that ‘he is one, and besides him there is no other’; and ‘to love him with all the heart, and with all the understanding, and with all the strength,’ and ‘to love one’s neighbor as oneself,’—this is much more important than all whole burnt offerings and sacrifices.” When Jesus saw that he answered wisely, he said to him, “You are not far from the kingdom of God.” After that no one dared to ask him any question. Which commandment is the first of all? Which is the greatest?

Recall that the scribes and the Pharisees obsess themselves over how to apply the Law. Recall that they view the Law as a measuring stick for holiness, and for authority. Inevitably that sort of thinking results in conflicting opinions. You have people competing with each other in this race to ultimate piety, and in order to get ahead, they are going to start insisting that particular parts of the Law are more important than others. If this part is more important, then I can focus more attention on that and become more authoritative and more holy than those other people. This became a real theological debate amongst Jews at the time. And so their question here to Jesus isn’t genuine interest in his thoughts. It’s a trap. It’s trying to categorize him. “Which kind of Jew are you?” They want to suck Jesus into their game of measuring sticks, to bring him down to their level, so that they have a definitive label, a definitive brand that they can curse him with. But Jesus doesn’t even hesitate. He has no interest in getting involved in their squabbles of who appears to be more holy, according to their own man-made scales. He surprises them all with not one, but two laws. Love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength. They were not doing this. They were loving themselves above all things. That is why they felt the need to measure holiness like that. God was not their focus. True holiness was not their focus. Their focus was their own pride. They only cared about their own vanity. Jesus further rebukes them with the second law. Love your neighbor as yourself. What good is spending all this energy creating a measuring stick if there is nothing to measure myself against? They needed competitors. They needed opponents. And they found them in each other. They found reasons to turn each other into enemies, so they could prove their own holiness. “I am not completely holy, but I am certainly more holy than them!” They have no love for one another. They love themselves, and even that is a false love. For one who truly loves themselves would love God first, and love themselves in reference to God. I love myself by pursuing true holiness, by pursuing right relationship with my God, and by holding fast to the Body of Christ, for I am a true member of that Body. But they love themselves in reference to nothing. They have no true love for self, and thus they cannot comprehend loving their neighbor as themselves. This is why Jesus emphasizes love of God first. You cannot love your neighbor if you do not first love God. And you cannot love God if you do not love your neighbor. Jesus’ words avoided the trap. But they also convicted the scribe. The scribe realized that what Jesus said is true, and that he had been led astray by petty squabbles rooted in pride. He realized that to love God and to love your neighbor is surely far more important than anything else in this world. It wasn’t until he learned this, until he turned his eyes toward Christ, that Christ said “You are not far from the kingdom of God.” Jeremiah 7:23-28 (NRSVCE) But this command I gave them, “Obey my voice, and I will be your God, and you shall be my people; and walk only in the way that I command you, so that it may be well with you.” Yet they did not obey or incline their ear, but, in the stubbornness of their evil will, they walked in their own counsels, and looked backward rather than forward. From the day that your ancestors came out of the land of Egypt until this day, I have persistently sent all my servants the prophets to them, day after day; yet they did not listen to me, or pay attention, but they stiffened their necks. They did worse than their ancestors did. So you shall speak all these words to them, but they will not listen to you. You shall call to them, but they will not answer you. You shall say to them: This is the nation that did not obey the voice of the Lord their God, and did not accept discipline; truth has perished; it is cut off from their lips. The agreement between God and man was that He would be our God, if only we would be His people. We were to follow Him. We were to obey. But we refused. Time and again, we refused. Whenever we began to walk down the path of righteousness, whenever God would set us aright by the words of His prophets or the messages of His angels, we would turn and look back to our old ways. Like Lot’s wife, we love our old ways more than we love God, and so we are always looking over our shoulder.

But it’s more than that. Here we are told that it’s not just a pattern of disobedience. It actually got worse. We became MORE indignant in our disobedience, more beholden to our own ways, and more resistant to the hand of God which is there to lead us. It became so bad that eventually we weren’t only disobeying, but we killed God’s only Son. That’s the level to which we will go to avoid giving up our own ways, to avoid the path of righteousness. We brand God as the enemy of righteousness, and put God on a cross. The words in Jeremiah are not for the ancient nation of Israel only. They speak directly to us. It is we who worshiped the golden calf. It is we who sought to return to slavery in Egypt rather than walk the path to the Promised Land. It is we who condemned John the Baptist. It is we who crucified Christ. We do all of this today, in our hearts and by our actions. We selfishly put ourselves at the center of our lives, when our lives ought to center on God. We stubbornly refuse to give up the hedonistic lives we have built for ourselves, like the people of Sodom and Gomorrah. And when a neighbor tries to correct us, we attack him. How dare he suggest that we are not righteous! We are far more righteous than he can ever know! I mean, just look at me, and how righteous I am! We are like the Pharisees. We have fooled ourselves and those around us into thinking our foolishness and wickedness is righteous. We don’t see the truth of our sin. For us, truth has perished. God sends His servants, and His prophets. Even today, they are all around us, speaking the words of the Lord, calling us to return to the path that leads to God. We have made a habit of ignoring them, of opposing them, even violently sometimes. But God is merciful. And in His mercy, He gives us the grace we need to turn away from our sin. He empowers us to walk the path and not look back. All we need to do is walk. All we need to do is to listen to the words of our shepherd, the Good Shepherd, who says: “Follow me.” Matthew 5:17-19 (NRSVCE) “Do not think that I have come to abolish the law or the prophets; I have come not to abolish but to fulfill. For truly I tell you, until heaven and earth pass away, not one letter, not one stroke of a letter, will pass from the law until all is accomplished. Therefore, whoever breaks one of the least of these commandments, and teaches others to do the same, will be called least in the kingdom of heaven; but whoever does them and teaches them will be called great in the kingdom of heaven." We come into the Sermon on the Mount today just after the Beatitudes. Jesus has already challenged our prejudices by proclaiming all those things “Blessed” that we associate with things cursed: the poor, the meek, the mournful, and the hungry. But now he is about to do something much more than merely upend our biases. He is speaking to a crowd full of Jews, who live under the strict confines of the Law, and telling them that he is not here to free them from that burden. He is here to bring the demands on the Law to new levels. He is here to demand more.

What follows is multiple examples of what he means by this. The Law says “You shall not murder.” But Jesus says if you are even angry with your brother, you are liable to judgment. The Law says you shall not swear falsely. But Jesus says you shall not swear at all, for everything you could swear by belongs rightly to God. To swear by anything, then, is to swear by God, calling on Him to vouch for your truth. As Romano Guardini says in The Lord, “[Jesus] no longer draws the line between right and wrong, true oath and false, but much sooner: between divine truth and human truth. How can man, who is full of untruth, place himself with his testimony beside God, the Holy One? Thus the commandment forbidding perjury is supplanted by a far profounder general love of truth, which does not swear at all because it knows and loves God’s holiness too well to associate it with any personal testimony.” [1] Over and over Jesus does this. “You have heard it said…” and “But I say to you…” Jesus takes what the Law demands, and challenges us to do more. While the Pharisees are overcome with piety in their rigorous enforcement of a strict adherence to the letter of the Law, Jesus tells us that they are not doing enough. Unless you are better than the Pharisees, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. But he is not merely referring to the Pharisees and their piety here. He is also referring to how the Law had been perverted, how the Law, which is from God, was taken possession of by man. Instead of working to place the hand of God on the people in everything they did, man took the Law and used it as a measuring stick for his own glory and his own power. The Pharisees and the scribes claimed authority because they had the Law. Jesus says in response that the Law is not yours to have, nor do you even understand the Law you claim to begin with. By their perversion of the Law, Jesus was to be killed (John 19:6-7). It was so perverted that they claimed divine authority to kill God’s own Son. This was not from God. This was the result of man. Jesus comes to not only set things right, but to raise them to new heights. He comes to subvert, but also to elevate. He comes to teach and demand of us the holiness the Pharisees claimed but would never achieve. He teaches true holiness. He has not come to abolish, but to fulfill. [1] Guardini, Romano. The Lord. Part 2, Chapter 1 Daniel 3:25, 34-43 (NRSVCE) Then Azariah stood still in the fire and prayed aloud: For your name’s sake do not give us up forever, and do not annul your covenant. Do not withdraw your mercy from us, for the sake of Abraham your beloved and for the sake of your servant Isaac and Israel your holy one, to whom you promised to multiply their descendants like the stars of heaven and like the sand on the shore of the sea. For we, O Lord, have become fewer than any other nation, and are brought low this day in all the world because of our sins. In our day we have no ruler, or prophet, or leader, no burnt offering, or sacrifice, or oblation, or incense, no place to make an offering before you and to find mercy. Yet with a contrite heart and a humble spirit may we be accepted, as though it were with burnt offerings of rams and bulls, or with tens of thousands of fat lambs; such may our sacrifice be in your sight today, and may we unreservedly follow you, for no shame will come to those who trust in you. And now with all our heart we follow you; we fear you and seek your presence. Do not put us to shame, but deal with us in your patience and in your abundant mercy. Deliver us in accordance with your marvelous works, and bring glory to your name, O Lord. Today’s reading might be unfamiliar to some of you, because it just might not be in your Bible. But I’m certain you are familiar with the story surrounding it. Azariah, if you remember back from the first chapter of Daniel, is called Abednego by the Babylonians (Daniel 1:7). And the first verse here mentions that Azariah is standing in a fire. He wasn’t alone, either. He had with him his two friends, Hananiah (Shadrach) and Mishael (Meshach). We’re looking at a section of the Prayer of Azariah, the prayer that Azariah broke into when he was thrown into the fiery furnace by King Nebuchadnezzar. And it is quite beautiful.

Remember that the three were thrown into the furnace because they would not worship the false gods of the Babylonians. They knew they would be thrown to the fire, and they didn’t even know whether God would intervene to save them. They only knew that they owed their worship to God alone, and to worship anything else would be worse than death. And because they knew this, they were to be put to death, at the moment of which Azariah is compelled to make one final plea for deliverance. What is missing from the start of this prayer is Azariah’s confession. He knows that what has happened to Israel, being in exile, and what has happened to the three friends here in the furnace, is because of their sin. God is just, and they have sinned against His justice, and for this they are suffering. “So all that you have brought upon us, and all that you have done to us, you have done by a true judgment. You have handed us over to our enemies, lawless and hateful rebels, and to an unjust king, the most wicked in all the world” (Daniel 3:31-32). Azariah knows that what they face is of their own making. But he has tremendous faith in God’s mercy. He knows that Israel has failed before, many a time, and God was always there to deliver them. God was always merciful. God promised much to the people of Israel, not least of which was that He promised to be their God. He promised to bless and keep them, so long as they kept to Him. Azariah admits their failure, he admits his own failure, and he does the only thing he can do. “With a contrite heart and a humble spirit,” he reaches, one last time, for his God. “Deal with us in your patience” as a parent is patient with their child, knowing their child will often fail. Deliver us, not for our own sake, but for the sake of your glory. We all know how this story ends, of course, Azariah’s plea is met with God’s merciful protection. An angel descends and drives away the flames, and the three break into a song of praise. “The Song of the Three Jews”. If the Prayer of Azariah is new to you, I recommend also looking up that song, as it is almost certainly missing from your Bible as well. Luke 1:26-38 (NRSVCE)

It’s the Solemnity of the Annunciation today, so it’s only fitting that today’s reading is Luke’s account of the Annunciation. There’s much to draw out of this passage. It has been central to the development of Mariology (that is, the theological study of Mary) over the years. The very first words that the angel Gabriel says to Mary are even the opening line of the Hail Mary prayer. Ave gratia plena; Dominus tecum; Benedicta tu in mulieribus. Hail, one who is full of grace! The Lord is with you! Mary was indeed full of grace. She had been given the greatest gift of all, for she was chosen by God to be the woman who brought the Savior into the world.

Her initial response seems silly, at first glance. “How can this be, since I am a virgin?” Surely any virgin, particularly one who was betrothed, who heard the news that she would bear a child would think “I suppose I will become pregnant by my husband.” But Mary presumes this is not the case. And why? Traditionally, Mary is believed to have been a “temple virgin”, or one who has been consecrated to a life of virginity. I am no expert on the Early Church, but as I understand it this largely comes from the Protoevangelium of James, which recounts how Mary’s parents, Anne and Joachim, consecrated Mary to God when she was only three years old in thanksgiving for giving them a child. This event is still celebrated every year by Catholics and Orthodox alike as a feast day, and provides some context which makes some sense of today’s reading. If Mary was a consecrated virgin, of course she would be wondering how it was possible she would become with child. She had vowed to remain a virgin forever. Surely she wasn’t to break that vow! The angel Gabriel then explains how it will be a miraculous conception, for “nothing will be impossible with God.” Throughout all of this, it can seem as if Gabriel is merely telling Mary what will happen. It can seem that Mary is just a cog in the wheel, a character with no agency. But her response is perhaps the most theologically significant point of this passage. “Here am I, the servant of the Lord; let it be with me according to your word.” Mary agrees, she says yes. The implication of this is that Mary could have said “no.” She could have refused Gabriel. But because God had filled her with His grace, she was empowered to say yes. God would not have forced Mary into this role against her will. And nor does God force our vocations on us. God calls us, and we must respond. Mary acts as an archetype of how we ought to respond. “Let it be with me according to your word.” Luke 13:1-9 (NRSVCE)

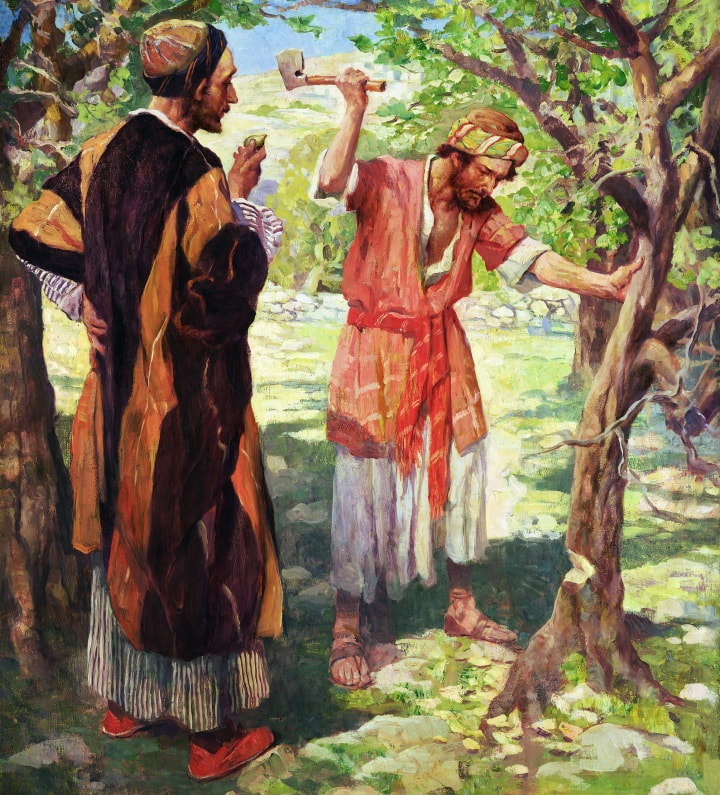

It’s easy to see the symbolism in the parable of the barren fig tree. God owns the garden, and He plants a fig tree expecting it to bear fruit. The fig tree could be taken to be Israel here, but also it could just refer to an individual. God sends a gardener to tend the tree, to help it along so that it would bear fruit. “For three years” the gardener does this (the duration of Jesus’ public ministry), and every year God sees no fruit is being brought forth. In His justice, He seeks to cut it down. But the gardener, Jesus, intercedes on behalf of the tree and promises to tend it some more, so that it might bear fruit. At this point Jesus has not yet concluded his public ministry, and there are a great many miracles yet to come. Jesus promises to tend us, to nurture us, to give us everything we need in order to bear fruit. But we must act as well. We must accept the pruning and take the fertilizer and the water and turn it into fruit. We must allow the gardener to work in our lives.

That this parable is given immediately after a call to repentance is no coincidence. Jesus is making a very pointed statement here. If you do not repent, you will die, as that is what sin results in. The Galileans who died were no worse than any other sinner. We are like them, and we will die just like them unless we repent. To put it another way, there were many fig trees in the garden. Many of them did not bear fruit, and they were cut down. But we who are alive are the fig trees which remain, with the gardener still interceding on our behalf. We still have the opportunity to repent, to allow the gardener to transform us so that we might bear fruit. The condition at the end of the parable is the most important, and what ties the call to repentance to the parable. The gardener does not promise that the tree will bear fruit. He only promises that he will provide everything which is necessary. It is up to us to respond to the gardener’s work in us. If we do not repent, we will be cut down, just as the Galileans were and just as the eighteen in Jerusalem were. Repentance, true repentance, involves a transformation from a barren fig tree to one that bears fruit. Not only one that lives, but one that brings new life, and supports the life of things around it. Absent repentance, we will bear nothing. We will remain barren, and eventually be cut down. Or perhaps a tower will fall on us. But the result is the same. Micah 7:14-15, 18-20 (NRSVCE) Shepherd your people with your staff, the flock that belongs to you, which lives alone in a forest in the midst of a garden land; let them feed in Bashan and Gilead as in the days of old. As in the days when you came out of the land of Egypt, show us marvelous things. Who is a God like you, pardoning iniquity and passing over the transgression of the remnant of your possession? He does not retain his anger forever, because he delights in showing clemency. He will again have compassion upon us; he will tread our iniquities under foot. You will cast all our sins into the depths of the sea. You will show faithfulness to Jacob and unswerving loyalty to Abraham, as you have sworn to our ancestors from the days of old. Micah is making a plea for God’s mercy here. Because of Israel’s sin, they have not been able to enjoy the rich pastures like those of Bashan and Gilead, as they were when they were first led to the Promised Land. Micah asks that God restore rich pastures to Israel. He acknowledges that this is only possible because of God’s mercy. Israel has sinned, and so their only path back to favor with God, their only way of receiving His blessings again, is for Him to have mercy on them. You can see the confidence Micah has that God will do so as well. God has shown He is merciful time and again with Israel, and God has already promised Israel will be restored. So Micah, recalling God’s past clemency and how God always delivers on His promises, expresses great hope that his prayer will be answered.

How often do we share Micah’s confidence in our own prayers? How often do we feel the weight of God’s mercy in our lives? It’s very easy to get into a routine with our spiritual lives, simply going through the motions. And there’s something to be said about that being a good thing as well, in the sense that when you are experiencing doubt or are going through troubled times and yet still “going through the motions” of your prayer and church routines, you demonstrate a strength of faith. A strength that says even when I am at my lowest, even when my doubt seems to take over my heart, I will still keep to my shepherd. I would argue that it’s moments like that which really prove our faith. It’s easy to remain faithful when times are good, when everything seems to be going our way and when it’s easy to believe. But it’s quite something else to be faithful when everything in your life is falling apart and when it feels as if your heart is entirely closed off from God. That’s where routine can help you to remain faithful. But routine isn’t all good. It can be easy to become apathetic in our hearts, even if our actions still indicate everything is as it should be. Your prayers can start to lack any real desire, any real contemplation, any real hope. You simply know the words and recite them as if reading them off a prayer menu. The pious reverence you show for the eucharist can lack any sense of awe and devotion. It’s times like that when we need to stop ourselves and reflect on the things we do in our spiritual lives. We need to recognize the seriousness of our condition. We need to reflect on the magnitude of God’s mercy and the promises He has made for us. And like Micah, we need to have hope that our actions, our faithfulness, is not for naught. We need to have hope that God will answer our prayers, that God will fulfill His promises, and that we will one day feed in Bashan and Gilead. Routine can be a very good thing for our spiritual lives. But it is best to interrupt routine with periods of reflection. Genesis 37:3-4, 12-13a, 17b-28a (NRSVCE)

Jacob loved Joseph more than his brothers because he was “the son of his old age.” The phrase is interesting. It could simply be referring to how a father loves his youngest, because the older he gets the more precious children become to him. But if that’s the case, surely Benjamin would be the “son of his old age” and not Joseph, as Benjamin was Joseph’s younger brother.

The title could also be referring to Joseph being wise himself. He is old in mind, being wise, but young in age, and thus he is “the son of his old age.” There are a great many Biblical commentaries out there which use this explanation. But the story, at least in today’s reading, paints a picture of Joseph that is not very wise at all. In fact, he seems almost oblivious to everything around him. He is the favored son, as he and his brothers all know, and he has dreams about how his brothers will all bow down to him (the dreams are in those omitted verses from today’s reading). He won’t stop talking about the dreams, and keeps reminding his brothers about how they will one day bow before him. They hate him for that. And then we see Jacob send Joseph out to find his brothers in the field, and Jacob wears his special robe (his “coat of many colors”), the sign of his position above his brothers. He is going to find his brothers, who hate him for his self-importance, wearing the sign of his importance. Surely someone who is wise would recognize the trouble he is stirring by stoking the tension with his brothers. So it seems to me it’s probably nothing to do with wisdom, and probably nothing to do directly with Joseph’s age. He doesn’t seem wise in this context, and he’s not the youngest of Jacob’s sons. I do recall reading about how traditionally a father would choose one of his sons to accompany him in his old age, keeping him near at all times to counsel him and prepare him to take over headship of the family. Unfortunately, I can’t seem to find anything on that right now. But that fits a bit more nicely with the “son of his old age” title in the context of this passage. Joseph is clearly chosen to take over headship once Jacob is gone. That is why Jacob gives him the robe. And while Joseph’s brothers are all out busy in the fields, Joseph remains with his father, despite Joseph being a teenager here and more than capable of joining his brothers. So “son of his old age” could simply mean that Joseph was the son chosen by Jacob to be the favored son who will take his place. That Joseph was chosen for this makes sense too when you consider that Rachel was the favored wife of Jacob (over Leah), and Joseph was the firstborn son of Rachel. We’re not told how long it is between Joseph’s birth and Benjamin’s, but it’s possible that Jacob had already chosen Joseph to be the favored son before Benjamin entered the picture. I’m not sure how much water that idea of “son of his old age” holds, but it seems to make the most sense of the context in which the title is given to Joseph here. |

ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed